Do Andalusians speak bad Spanish? Of course not

Over the weekend I read an article called “No, los andaluces o los latinoamericanos no hablan un mal castellano”. (No, Andalusians and Latin Americans don´t speak bad Spanish). It caught my eye because I have lived in both Latin America and Andalusia. In fact, my Spanish vocabulary is peppered with words from Latin America, leading my friends to joke about my “incorrect Spanish”. However, many of them are Andalusian, and within Spain, the Andalusian dialect is often looked down upon and considered improper. I´m not going to lie, it did take a while to get used to the accent, dialect and slang. Four months in, I´m still often left with a blank expression when someone tells a joke.

Nevertheless, can we really call regional dialects bad Spanish? Moreover, where has this idea come from?

It is often said that the best, purest Spanish is spoken in Valladolid. The article looks at why this is. Could it really be true that Latin Americans and Andalusians are less educated or perhaps lazy? As the article states, a lot of is this related to power relations. The author indicates that the area around Valladolid, Madrid, Toledo (the areas that speak the most “correctly”), is where the political power of the Spanish speaking world has been held for hundreds of years. Therefore, these areas have decided what is “correct” and what is not. Since language is an ever-changing phenomenon, it is constantly evolving. The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis this tells us that language is intrinsically linked to culture and the experiences we live. If this is true, how can we expect language to evolve in the same way in Madrid, Andalusia, Mexico, and Peru etc. If the power relations were reversed and Mexico, for example, had held the political power for centuries, wrote the rules for standardisation and the dictionaries, would the Spanish spoken in Valladolid be incorrect?

The article goes onto explain that this is typical everywhere, using the United Kingdom as an example. In my home country, the power has been based in the South of the country and regional accents from Manchester, Liverpool and Edinburgh being considered “improper”. Now you can see why this article was so interesting for me, it seems like I will never win. I was born in Manchester, and my Spanish is probably now some mix of Latin American, Andalusian and Guiri dialects.

These prejudices can cause problems for speakers of a non-standard dialect in situations such as job interviews and in court. Studies have shown that speakers with non-standard accents are judged negatively and are less likely to be offered the job. It has also been shown that judges and juries can look unfavourably on regional accents. This amounts to discrimination. In 2018, we no longer accept sexism, racism or homophobia. So why does the stigma still exist regarding regional accents?

Another interesting angle that this article discusses is the difficulty regional accents cause in technology. Voice recognition is becoming more and more popular. If you speak with a regional accent, you are probably already aware that apps like Siri and Alexa can be interesting to say the least. I personally have never been able to get Siri to do what I want it to do. If you are interested in this, you can hear CBLingua´s Carolina talking about this technology and the translation industry here.

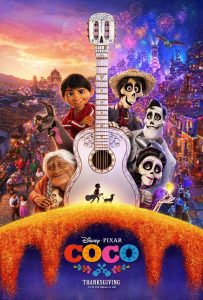

This topic also affects cultural production. Both Coco (which won Best Animated Film at last night’s Oscars) and La Peste have come under fire for their respective Mexican and Andalusian accents. Is it right that every piece of culture produced in the Spanish language should be spoken or written in so-called “proper Spanish”? Why should the characters in Coco, a film about Mexico and Mexican traditions speak Spanish from Madrid? It would appear that cultural and linguistic hegemony is still alive hundreds of years after decolonisation.

This topic also affects cultural production. Both Coco (which won Best Animated Film at last night’s Oscars) and La Peste have come under fire for their respective Mexican and Andalusian accents. Is it right that every piece of culture produced in the Spanish language should be spoken or written in so-called “proper Spanish”? Why should the characters in Coco, a film about Mexico and Mexican traditions speak Spanish from Madrid? It would appear that cultural and linguistic hegemony is still alive hundreds of years after decolonisation.

This also throws up interesting ideas for translation. When we are tasked to translate something that has a clear regional and cultural identity what should we do? Should we translate it into a standardised version of the target language? Should we translate it into a regional dialect of our target language? How about when we are interpreting in a court environment? Could interpretation and the interpreter’s dialect and language sway the decision of a judge and jury? This sheds some light on the responsibilities we sometimes have as translators.

I´d like to finish off by highlighting a phrase in particular “Podemos dejar de juzgar a las personas por cómo hablan o cómo escriben y empezar a prestar más atención a lo que dicen, que es lo realmente importante” or “We can stop judging people for how they speak or write and start paying more attention to what they say, which is more important”. It is time we put an end the historical inequality linked to regional dialects and start to embrace linguistic diversity.

Does your native language have any regional dialects? If you have any thoughts on this we´d love to hear from you!